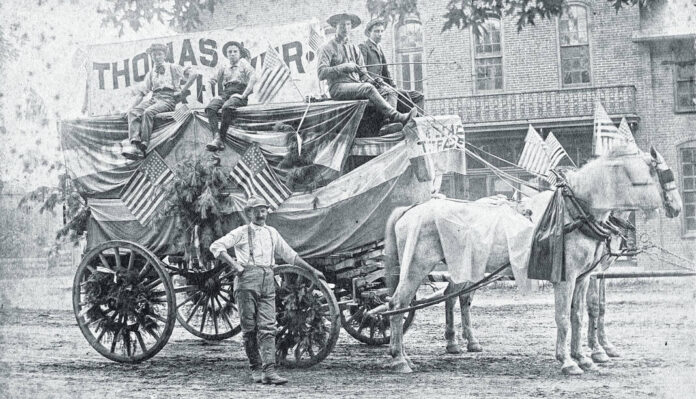

The float of the Thomas Hover Ice Company is shown in this photo donated to the Allen County Historical Society in June 1946 by the Mont S. Irwin, the wagon driver. Irwin said the photo is from 1888, although the Hover float also appeared in the 1891 Labor Day parade. Irwin said he decorated the wagon the Sunday before Labor Day, then went out Monday morning and delivered ice with it. After hitching an additional team of horses to the wagon, Irwin said he drove the wagon in the parade, after which he unhitched the extra team of horses and delivered ice for the remainder of the day.

LIMA — Lima was a little late recognizing the new Labor Day holiday, but when it did on a Monday in September 131 years ago, the celebration was a doozy.

The “Workingman’s Fourth of July,” as the newspapers called it, featured a parade long enough that when the first units had completed an eight-block square they caught up with the tail-end, an acrobat dangling from a hot air balloon, speeches, concerts, fireworks, ball games and a foot race in which a third of the field was knocked out by a misbehaving horse. At one point during the races, the militia was brought in to restore order. Earlier in the day, a runaway team of horses forced city fathers to leap for their lives from a carriage.

Everyone — or nearly everyone — agreed the day was a big success.

Writing a week after the event, the Lima Clipper, the local voice of the temperance movement, bemoaned the presence of brewers (represented, it claimed, by 11 wagons in the parade) and liquor dealers and, like a literature prof doing a deep dive into a classic, found hidden messages and symbolism on the evils of alcohol everywhere. A man impersonating a king atop a brewer’s float was apt because, the Clipper wrote, the brewers and distillers “together with their allies, the saloon keeper, have well-nigh subjugated Christendom.” The placement of a second-hand furniture dealer’s float behind a brewer’s appeared “to the thoughtful” to be “very suggestive of the grimy squalid home of the poor besotted victim of the liquor traffic from whom much of it (used furniture) is purchased…”

However, writing on Sept. 8, 1891, the day after the event, the Lima Daily Times expressed the sentiment of those not looking so critically at the celebration. “Labor Day, 1891, has come and gone — but not from the memories of the thousands who participated in its celebration in Lima,” the newspaper wrote. “It was the biggest day and the greatest demonstration this city has ever seen.”

The celebration of the first Monday in September as Labor Day was begun by the Knights of Labor in 1882. Colorado passed the first act making the day a legal holiday in 1887 and other states, including Ohio, soon followed. According to a 1978 article in the county historical society’s Allen County Reporter, the first Labor Day celebration and parade in Lima was in 1888 but “the grandeur usually associated with this holiday seemed not to occur until 1891.”

Blessed with blue skies and benefiting from a Saturday rain that knocked down the dust on the city’s dirt streets, Monday, Sept. 7, 1891, was perfect for a parade. “The world and his wife and children were all out,” the Times proclaimed in a headline the following day. “Quite early in the morning, the people began to arrive from the country in vehicles, and the trains brought in their hundreds from surrounding towns,” the newspaper wrote. “Those, who had been for days, and during most of the night before, preparing displays for the procession, turned out their wagons hours before the time for the starting of the parade; and the Public Square and all the streets leading into it were crowded with floats and vehicles of all kinds, and with a perfect multitude, much before ten o’clock.”

The “perfect multitude” was more than organizers had planned for and “they began to fear that they would have their hands more than full,” the Times wrote, adding, “These fears were verified in the utter impossibility to get the mixed-up masses of labor organizations and mercantile and manufacturing displays into the order intended.” Finally, they just did as well as they could and sent the procession marching west on Market Street, north on McDonel Street, east on Wayne Street and south on Main Street, where, according to the newspaper, “the head of the procession came into contact with the tail before the latter had fairly started out.”

The procession was led by carriages containing the day’s speakers and city leaders, followed by the firefighters, letter carriers, police, the Second Regiment Band of Kenton, the Lima City Guards and so on. The floats followed, including one from the city’s florists “handsomely decorated with flowers, plants and vegetables, containing a load of attendants, including two very pretty girls, who gave out bouquets along the way,” the Times wrote. Popcorn balls, the newspaper added, were thrown from a float representing the Banta Candy Company “into willing hands in the street.”

Floats or wagons representing merchants, manufacturers and unions passed by the thousands lining the parade route. “Farmer Montague came along with a load of melons.” the times noted. “The Enterprise Oil Company slipped in with its tank full. Shaffer Bros., the Cridersville nurserymen, had a neat wagon decorated with evergreen and other trees and loaded with people. Sealts Bros. (wholesale grocers) sent out their three horses abreast.”

After the parade was delayed four times by streetcars, it was decided to abandon part of the planned route and head east on Market Street toward the county fairgrounds, which was at the Lima Driving Park on the present-day site of Lima Memorial Health System. By the time the parade reached the fairgrounds, although half the units and many marchers dropped out along the way, enough remained to fill the half-mile track where they were greeted by ten to fifteen thousand people, the Times estimated.

During the parade around the racetrack, the horses pulling a carriage carrying four city officials bolted. “A line caught in the harness and the boy driving could not control the team,” the Times explained, adding that three of the four officials jumped, tumbling in the dirt of the racetrack, while the fourth stuck with the carriage and helped the driver regain control.

At two o’clock the speeches began before the grandstand. But, because of the large crowd and the noise of a “brisk breeze,” only those close to the speakers heard them. The main speaker, a union official from Detroit, was frequently interrupted by “some people in the grandstand who evidently didn’t care to hear a good speech or have anybody else hear it,” the Times noted. “Men with hair on their faces, who should have known better, were engaged in this,” the newspaper added, “and some of them will not be forgotten.”

Following two bicycle races, a foot race was called. “Kent W. Hughes, George Marth, Fred English, Elisha Athey, Gurkel, and a colored fellow named Wilson entered the arena,” the Times wrote. However, according to the newspaper, “the greatest difficulty was experienced opening up the crowd that packed the racetrack in front of the grandstand to give running room.”

Marshal Frank Morris was attempting to provide room from the back of his horse when the runners were started, which spooked the horse, which “began charging backward colliding with two runners — Athey and English,” the newspaper wrote. “The police soon quelled the disorder, and the militia with fixed bayonets was called upon to open the track, which they did most effectively.” Hughes, the son of a judge, came out the winner in the reduced field.

A balloon ascent and parachute descent by “Prof. Young” then thrilled the crowd, with the professor clinging to a trapeze bar while performing tricks. “It made the ladies hold their breath to see him flying heavenward at a rapid rate suspended by his toes from the bar,” the Times wrote. “The daring professor landed near a big haystack about a half mile south of the fairgrounds.”

A fireworks display, during which “all streets adjoining the Square were packed with humanity,” thrilled the crowds downtown.” A “well-attended” concert at Music Hall followed, and “the merry dance was kept up to a late hour,” the Times wrote.

SOURCE

This feature is a cooperative effort between the newspaper and the Allen County Museum and Historical Society.

LEARN MORE

See past Reminisce stories at limaohio.com/tag/reminisce

Reach Greg Hoersten at [email protected].