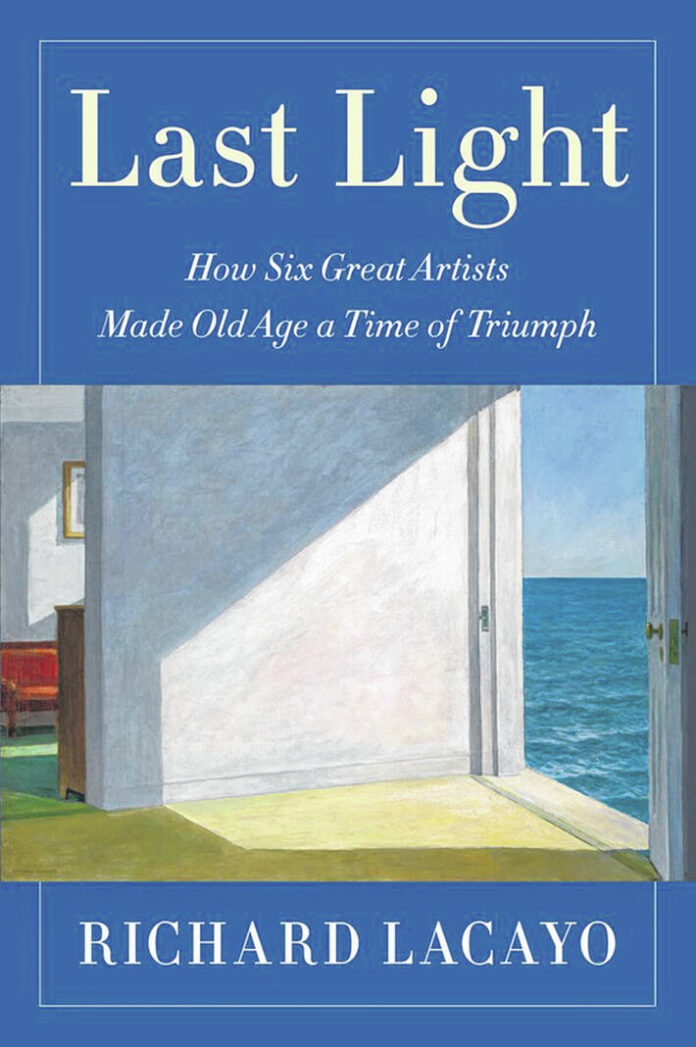

“Last Light: How Six Great Artists Made Old Age a Time of Triumph” by Richard Lacayo; Simon & Schuster (384 pages, $35)

Plug the phrase “rising young art star” into Google and a mountain of results will turn up. Rising young art stars are showing at museums, rising young art stars are moving merch at Art Basel, rising young art stars are sitting for studiously casual photos in fashion magazines. We live in a society that prizes youth, and the art world is no different. The conventional wisdom being that an artist’s most innovative years are in the first half of life.

Richard Lacayo might beg to differ. The former Time magazine art critic’s latest book, “Last Light: How Six Great Artists Made Old Age a Time of Triumph,” which was published last fall, tracks the works of artists who continued to push themselves — and the boundaries of art-making — right up to the end. And in some cases, the importance of this late-in-life work wouldn’t be understood until a generation or more had passed.

Take Claude Monet, one of the artists featured in the book — who lived to the ripe old age of 86 (he died in 1926) and continued to work until the very end of his life.

The French Impressionist’s late canvases came at a fraught time. He was fighting cataracts and racked with grief over the loss of his wife, Alice. Impressionism had slipped out of fashion, and a younger generation of brash upstarts, including Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, were making noise with Cubism and other fresh concepts. Monet had come to represent the institution, inspiring yawns in the avant-garde.

It might not have seemed so at the time, but Monet was still in possession of “a young man’s audacity,” writes Lacayo. And, “in his last decades it was wedded to an old man’s achieved mastery of his art, the fruit of Monet’s lifelong ‘researches’ into light, color, and the most potent ways to represent nature.”

Many of his late canvases — among them, a suite of eight large-scale water lilies paintings that for nearly a century have occupied their own galleries at the Musée de L’Orangerie in Paris — broke with conventions of how landscape was presented. Some do away with perspective and vanishing points, instead showing the artist turning his gaze exclusively to the surface of his pond at Giverny — a view that shows water without any land to put it in context. As a result, some of these canvases can feel disorienting and wildly abstract.

“Monet was entering — was inventing — an entirely new kind of pictorial space,” writes Lacayo. “The pond is simultaneously a mirror that shows us the sky and the trees above it, a membrane that the water lilies ride upon and a window into the depths below, dimly alive with long filaments of moss and wavering grass. Every brushstroke had to imply one or more of those interlocking dimensions.”

The paintings in the Orangerie, bequeathed by the artist to the nation of France in the wake of World War I, are epic in scale — with vast swathes of canvas turned over to gently pulsing color that echo only the vaguest notion of form.

The reviews were mixed when they were unveiled in the 1920s, with some critics dismissive of Monet’s preoccupation with color and light. But the water lily paintings, as Lacayo notes, gained renewed traction with the advent of New York’s Abstract Expressionists, artists intrigued by the concept of “all over” painting, in which canvases were entirely covered in gestural brushstrokes.

In Monet’s work, there was precedent for Jackson Pollock’s drips and Helen Frankenthaler’s pours — something that became evident when New York’s Museum of Modern Art staged a major exhibition of Monet’s work in 1960. His late canvases made the rowdy New York School seem just a little less radical. As Andy Warhol once stated on the matter: “It was as if somebody said, ‘Why look at Monet, that sweet old man. He was doing all these wild things before you were born.’”

“Last Light” also devotes chapters to Titian, Francisco Goya, Henri Matisse, Edward Hopper and Louise Nevelson. The list is lamentably all Western canon. (Lacayo drew on existing biographies, which is limiting.) But it provides a fresh way of looking at artists you might think you know well, since it inverts the narrative typical of a lot of biographical writing, with its focus on the creative energies of youth followed by the inevitable march toward mannerism and death.

Lacayo instead uses youth as context for what would come later — and in some cases, that late exuberance is inspiring. “Must I stop work even if the quality deteriorates?” asks Matisse, exasperated that anyone might challenge his devotion to his studio. “Each age has its own beauty.”

The book devotes about 50 pages to each artist, and each of these chapters reads like a compelling mini-biography (you don’t have to know anything about the painters to appreciate them). In addition, they can be read front to back or dipped into at random; a generous helping of images, along with some lovely endpapers, help illustrate Lacayo’s points.

What ultimately makes this worth reading is the writing: Lacayo avoids the artspeak in favor of a tone that is erudite but personable. Goya, a Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries whose early years were marked by a lightness of subject, grew darker and more mystical as he aged, reflecting on the barbarities of war — inspired by the Peninsular War, whose purges he survived. “Goya’s late work was an incendiary device that didn’t explode until it landed in the lap of the 20th century,” Lacayo writes of the painter, “an era terrible enough to understand it.”

In many ways, longevity — in life and in the studio — enhanced the posterity of these artists. Some of Goya’s most masterful works, and his most remembered — the grotesque Black Paintings, his horror-filled etchings series “The Disasters of War — were created in the last two decades of life.

“If he had died in his early sixties,” writes Lacayo, “he would still be remembered as an artist of charming genre scenes in his youth, a superb portraitist and printmaker in his maturity and a gifted satirist, but not as one of the most influential artists of all time.”

The art industry fetishizes the young, but “Last Light” makes the case that it is unwise to write off the olds. Because life can be long, the afterlife even longer.

Among the drawings Goya made in his last couple years of life is an image of a frail old man walking with the aid of two canes. It is captioned, “Aun aprendo” (I’m Still Learning).