General Motors Co. is moving to restore cost-of-living adjustments for some workers in talks with the United Auto Workers — a benefit the automaker nixed during its historic bankruptcy nearly 15 years ago.

As the union’s strike against all three Detroit automakers entered a 25th day Monday, GM said its latest offer to the union made last week would reinstate cost-of-living allowances for employees at max wages starting in year two of a deal with the UAW. The automaker also said it would improve retirement security, with the company contribution increasing from 6.4% to 8% of wages for active in-progression employees.

But it’s clear GM remains behind its crosstown rivals Ford Motor Co. and Stellantis NV on several UAW demands. GM hasn’t moved from 20% wage increases over the life of the agreement and is still only willing to cut the time to make it to the top wage rate in half to four years. Ford has moved to a three-year progression.

“Ford and Stellantis have agreed to reinstate the cost-of-living allowance and GM isn’t far behind,” UAW President Shawn Fain said in a Facebook Live presentation on Friday.

GM on Friday did agree to include joint-venture battery manufacturing workers in its master agreement, which the union expects the other two companies to follow, despite not yet having a battery plant up and running in the United States. GM on Monday did not provide details on how it will bring its battery plants into the master agreement it has with the UAW.

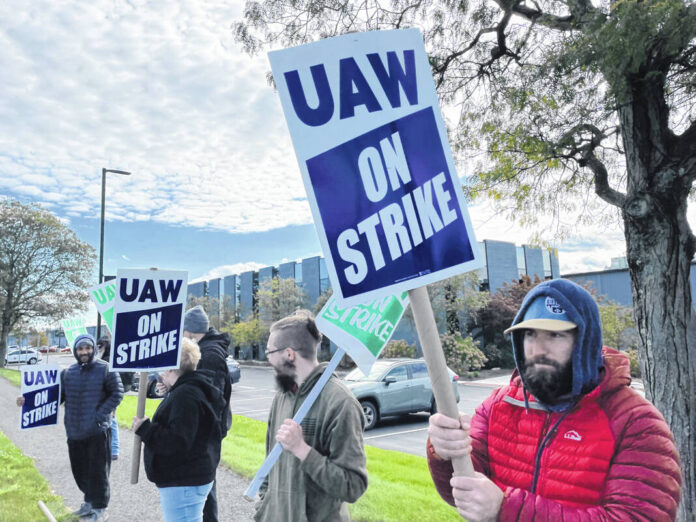

Ripple effects from the strike at selected plants continued to grow Monday and rank-and-file members at Mack Trucks Inc. started their own picket lines after rejecting a tentative agreement.

The deal between the Detroit-based union and the Volvo Group-owned heavy truck builder received a 73% no vote on Sunday. It promised most workers would receive a 19% wage increase over five years, including an immediate 10% raise upon ratification. It also included a $3,500 ratification bonus, an increased 401(k) contribution and reduced the length of time to the top wage by one year to five years. The UAW represents roughly 3,900 workers at Mack Trucks in Pennsylvania, Maryland and Florida.

These workers are in a different industry than the 146,000 UAW members at General Motors Co., Ford Motor Co. and Stellantis NV — 25,300 of whom are on strike. Heavy truck manufacturing has distinct cost structures, competitive pressures and consumer bases. Still, the vote by a significant majority of Mack workers against the deal sends another signal to the union and the Detroit Three of the high expectations of the rank-and-file for new agreements following a public negotiations process, high rates of inflation and major profits at the companies.

Mack strike impact

Art Wheaton, director of labor studies at Cornell University, said that the high expectations UAW leaders have stoked for Detroit Three workers “absolutely” played a role in Mack Trucks workers’ rejection of the agreement, and in the narrow contract ratification approval by Ford workers in Canada last month. Mack workers likely also were paying close attention to the deal between the Teamsters and UPS that was widely regarded as a win for workers.

“They keep seeing what’s going on and what everybody’s promising or what they’re after and saying, ‘Gee, ours doesn’t sound that good,’” said Wheaton.

Although members rejecting tentative agreements is not uncommon, Wheaton said it can hurt union leaders’ credibility at the bargaining table since they had reached a settlement and endorsed it to their members.

The Mack vote “shows the Detroit Three that they have high expectations and you’ve got to get this thing ratified,” he said. “(UAW President Shawn Fain has) raised expectations. … He wants a record contract. He wants it to be a blockbuster. So if you deliver any less than that, it becomes a challenge to get it ratified, as they just found out at Mack.”

Marick Masters, a labor expert at Wayne State University, called the 73% vote to reject the deal “very telling that they expected more” and noted that workers might have been dissatisfied with wage increases being spread across five years instead of four.

“Not getting COLA and other things probably caused them to look unfavorably upon this contract compared to what they thought was attainable,” he said. “And so I think what it does in terms of positioning the UAW for its negotiations with the Big Three is to … realize they’ve got to have a really good tentative agreement before they can take it to the membership.”

Although members on picket lines have responded exuberantly to the livestreams and communication from their union on the state of talks, it’s created a “double-edge sword,” said Susan Schurman, a distinguished professor at Rutgers’ School of Management and Labor Relations.

“At one point,” she said, “you have to ask: Have you extracted what you’re going to extract, and when it’s time to get a tentative agreement, will you be able to persuade (the rank-and-file)? Or do they think there is more worth holding out for when there may not be? That’s a tough call for any union leader. It’s the toughest decision that Shawn Fain is going to make.”