LIMA — Top administrators from Allen County Children Services doubted a 12-year-old boy when he disclosed that he was being sexually assaulted by a licensed foster parent.

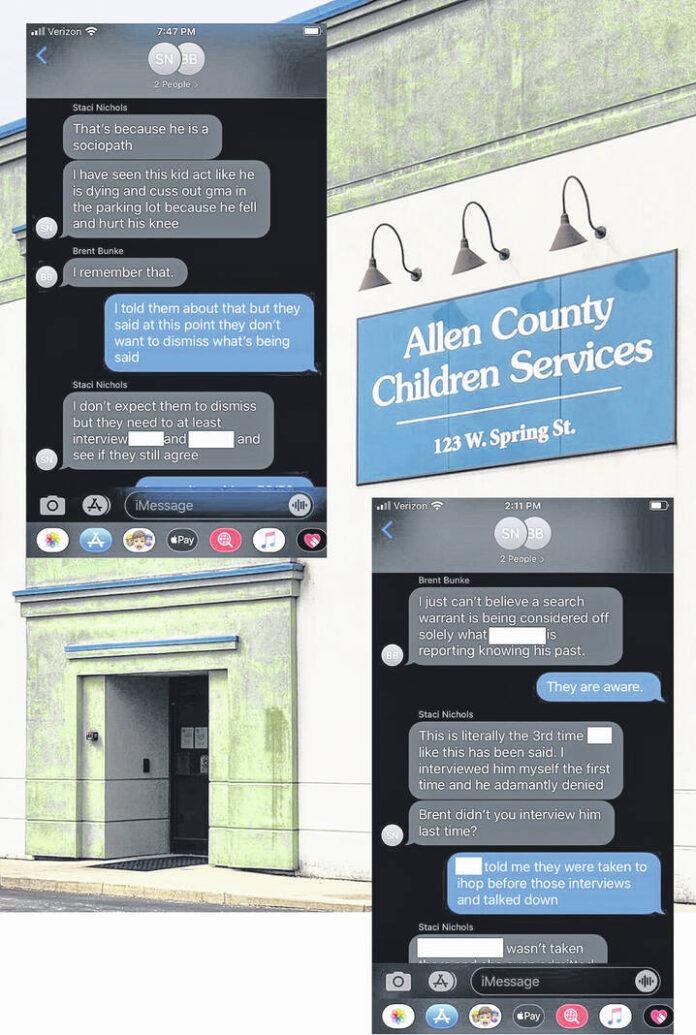

“I just can’t believe a search warrant is being considered off solely what (redacted) is reporting knowing his past,” Brent Bunke, a former program administrator who oversaw the agency’s adoption and foster care division, wrote in a text message to colleagues, according to messages recovered by the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation.

“If they find out (redacted) is lying I hope they charge his little (expletive) for this (expletive),” Staci Nichols, a fellow program administrator from the agency’s intake division who has since resigned, wrote in another text message that evening.

The text messages were sent on May 20, 2020, after the 12-year-old boy ran to the Allen County Juvenile Detention Center and disclosed that Jeremy Kindle had sexually assaulted him.

A judge eventually sentenced Kindle to 94 years in prison after Kindle pleaded guilty to 20 of 65 counts against him. His partner, Scott Steffes, received a 47-year prison sentence for his role in the abuse. Together, the couple abused seven boys, who were between the ages of 11 and 18 at the time Kindle and Steffes pleaded guilty.

An officer who overheard the boy talking with a Children Services caseworker asked if he should contact a detective from the Lima Police Department to investigate.

“No, probably not, not right now,” Bunke told the caseworker, according to body-worn camera footage which captured the caseworker’s Facetime call with Bunke and colleagues.

Bunke and Nichols were shocked: Twice, they and Children Services Director Cynthia Scanland had investigated similar claims about Kindle, but dismissed the allegations as a child dependency case without notifying law enforcement or initiating a third-party investigation.

The Lima News reviewed investigatory records from BCI’s investigation into Scanland, whose criminal charges were dismissed in January, to provide a fuller account of how agency officials mishandled investigations into Kindle before his arrest three years ago.

The records show several missteps taken by officials who doubted the credibility of the children involved because of their history with the agency.

Bunke and Nichols resigned over the scandal, while the Children Services board terminated Scanland’s contract after an Ohio Bureau of Investigation inquiry into why the previous allegations were not reported to law enforcement.

Scanland declined to comment for this story through her attorney, who similarly declined to comment. Bunke and Nichols did not respond to multiple notes left at their homes before publication. The Lima News relied on audio recordings and interview summaries from BCI to understand their thinking about the case and what went wrong in their investigations.

Signs of trouble

The first report came through in June of 2019: Kindle promised a child gifts in exchange for sex acts, a woman told Allen County Children Services, referencing a conversation she had with the child’s sibling.

State administrative code and internal policy show the report should have been referred to law enforcement or an outside child protective services agency given the nature of the report — a felony — and Kindle’s relationship as a licensed foster parent and on-call nurse for Children Services.

The investigation stayed in-house instead.

Nichols and Scanland interviewed the boy, who reportedly denied everything, and screened the report into Ohio’s child welfare database as a dependency case — preventing other child welfare agencies searching for foster or adoptive homes from seeing the original allegation about Kindle, BCI records show.

Four months later, a teacher called Children Services with a new sexual abuse tip about Kindle. A student told the teacher about an alleged video in which a boy living in the Kindle-Steffes household described sexual abuse occurring inside the home.

Agency officials investigated the couple for a second time, concluding the allegation was likely false after multiple children denied the claims, although it is unclear whether they spoke to everyone residing at the Kindle-Steffes household before making their determination, records show. The interviews were not recorded.

Months later, the child’s grandmother told a caseworker that Kindle and Steffes reportedly took the boys to IHOP and talked them down beforehand, according to a text message the caseworker sent to Bunke and Nichols obtained by BCI.

‘System kids’ and a foster parent’s reputation

Still, administrators screened the report in as a dependency case, overriding an initial sexual abuse entry, noting that one of the boys at the center of the allegations was living with Kindle and Steffes while his grandmother had custody, according to a screen-in report signed by Scanland, Bunke and Nichols from the October 2019 call obtained by BCI.

On both occasions, agency officials failed to notify law enforcement or intiate a third-party investigation.

Allen County Prosecutor Juergen Waldick asked BCI to investigate so he could determine whether he needed to appoint a special prosecutor.

Records show Bunke, Nichols and Scanland blamed one another for their mishandling of the reports.

Bunke and Nichols told investigators Scanland reportedly pressured them to screen the reports in as dependency cases over their objections because the complaints originated from “system kids” with a history of behavioral issues. The former agency director reportedly told them to re-screen the case if any of the children disclosed abuse, records show.

Why not contact law enforcement? “She didn’t want to negatively impact a foster parent’s reputation, and their job potentially, without having more information and more details,” Nichols said, according to an audio recording released by BCI.

Scanland denied those allegations in a separate interview with investigators, claiming she was asked to participate in the screening process due to the complex nature of a report involving a foster parent and children known for making false accusations.

“It was not an order from me,” Scanland said, according to an audio recording of the interview.

“These children never disclosed any sexual abuse to me,” Nichols said in a follow-up interview with BCI. “I have devoted 20 years of my life to protecting kids.

“I would not know about a kid being sexually abused and let them stay there, and I stayed up all night long thinking that I did something wrong, thinking that I’m going to lose my own kid and go to jail over this, but I didn’t (expletive) do anything.”

A direct line to the director

Kindle regularly communicated with Scanland when he had an issue with a caseworker or supervisor, such as the time he and Steffes were short on training hours needed to renew their foster license in November 2019, Bunke told investigators.

Kindle reportedly bragged to his caseworker that Scanland would waive the hours for him, though Bunke claims he warned Kindle the agency wouldn’t renew his license if he didn’t complete his training.

Investigators allege Scanland and Bunke manipulated the training documents by crediting Kindle and Steffes, who as foster parents were legally required to finish at least 40 hours of training apiece every two years to keep their license, for other activities before their license expired.

Scanland described it as a one-sided relationship, telling investigators that Kindle was an attention-seeker who sent her unsolicited text messages that she found “rather annoying.”

Kindle and Steffes weren’t the only foster family with direct access to Scanland, who reportedly shared her personal cellphone number with several foster families, BCI records show.

Investigators allege Scanland changed another sexual assault report in the state’s child welfare database after a different licensed foster couple complained that an allegation against their child, who was accused of sexually abusing a foster child, prevented them from fostering children.

The allegation was reportedly changed from indicated to unsubstantiated in April 2019 at Scanland’s direction, as she claimed there was a problem with the initial investigation, according to BCI summaries about the case.

A broken agreement, and a case dismissed

Scanland told investigators that the agency’s memorandum of understanding (MOU), which outlines how and when Children Services should work with law enforcement and child victim advocates to investigate abuse, was “regularly not followed by parties involved,” so much so that the document reportedly wasn’t signed when she came to the agency.

“We don’t go by this,” she said, according to the audio recording. “It’s not referenced a lot.”

A copy of the MOU provided to The Lima News, apparently dating from 2011, shows the signature of Scanland’s predecessor, Scott Ferris, and other county agencies named in the agreement.

A spokesperson for Children Services said that the agency cannot speak to Scanland’s comments, but said the MOU “is in place and followed” under current leadership. The document is undergoing revisions to comply with recently passed legislation, he said.

Current Executive Director Sarah Newland, who was appointed by the Children Services board when the board terminated Scanland in 2020, did not comment on the case. But she told investigators in 2020 that the situation could have been prevented had officials followed the MOU and notified law enforcement when the first complaint about Kindle was reported 11 months prior.

“That’s the frustration is if (officials) would have just followed this, we would not be in this situation,” Newland said, according to an audio recording of her interview with BCI.

Authorities charged Scanland in September 2020 with three counts of tampering with records, a third-degree felony; one count of obstructing official business, a fifth-degree felony; and one second-degree misdemeanor count of dereliction of duty for her role in mishandling the reports about Kindle.

Days before her February trial, Special Prosecutor Gwen Howe-Gerbers dismissed the charges in exchange for Scanland’s agreement not to teach or work for another child protective services agency in Ohio for 10 years.

The state retained the right to refile charges if Scanland violates the terms, but agreed not to oppose a motion to seal the records in 10 years if Scanland complies.

‘Mr. Kindle and Mr. Steffes are the ones accused’

A press release issued by the Children Services board when Scanland was terminated in 2020 outlined reforms the agency planned to make. Employees could go outside the chain of command if they felt pressured not to report, the release said, while promised structural changes would improve transparency and morale among staff.

Agency officials have not talked about the case or reforms since the press release was issued two-and-a-half years ago.

“Our top priority is to keep kids safe, and that means zero tolerance when employees show poor judgment as in this case,” Jennifer Hughes, then the CSB president, said in the press release from 2020. “I believe our employees had the best intentions, but procedures – especially these – are in place for a reason, and by board action today we sent the message that we will not tolerate deviation from our own internal rules and common sense.

“It’s important to remember that Mr. Kindle and Mr. Steffes are the ones accused of terrible crimes in this case, and we continue to cooperate with law enforcement,” Hughes said then. “The agency has worked hard during these trying times to continue our mission of serving the children of Allen County, and we’re committed to doing our best to ensure that something like this never happens again.”

Newland echoed those sentiments recently when asked about the case.

“What I can say is that everyone in this building is committed to the mission of preventing child abuse and neglect,” she said. “These caseworkers work tirelessly each day towards prevention — long days, long hours — and that’s our goal. That’s our mission. As the director, I’m the person that makes sure that that happens every day.”