“The absence of your laughter is not a choice I made / Though my life was not an option, I still offered it for trade.”

Those are lines from the poem, “Turn Back Time,” by author Bill Mulholland, of Lima.

Mulholland began writing poetry as a way to cope with the overwhelming grief he and his family experienced after the loss of Cecilia “Cece” Raen Eversole on June 15.

Cece, born Nov. 9, 2018, was the granddaughter of Mulholland and his wife, Kendra. Her death at age 3 1/2 from Dravet (pronounced “dra-VAY”) Syndrome provided the impetus for his first book, “Poetry for Coping with Grief and Loss.”

Mulholland hopes that the poems will help others who are dealing with the pain of loss. He also wants to heighten awareness of Dravet Syndrome.

What is Dravet Syndrome?

Dravet Syndrome is a genetic form of epilepsy that begins in the first year of life, according to the National Institutes of Health. The prevalence of Dravet Syndrome is approximately one in 30,000 people. It is characterized by temperature-sensitive seizures that are often resistant to standard treatment. Many children with Dravet Syndrome develop developmental delays following the onset of seizures.

Approximately 80% of children with Dravet Syndrome have a mutation in the SCN1A gene, which affects the function of brain cells, called neurons, according to the NIH. The gene SCN1A encodes the instructions to make a protein in the brain called a sodium channel. Genetic variants that affect the SCN1A sodium channel impair the flow of sodium ions into neurons in the brain and lead to overactivity of neurons which can contribute to seizures and epilepsy.

Mulholland and his wife, Kendra are both certified nurse practitioners. They approached their granddaughter’s condition in much the same way they did their other patients. They considered the history of the illness and the symptoms being experienced while repeatedly asking themselves, “What am I missing?”

“I read more about neurology (while attempting to diagnose the problem) than I ever did in school,” Mulholland said.

When the Mulhollands read about Dravet Syndrome, they considered the condition as high on their list of possible diagnoses.

“I didn’t want it to be (Dravet Syndrome),” Mulholland admitted.

After several weeks, Cece’s diagnosis of Dravet Syndrome was confirmed at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus following extensive genetic testing.

The first seizure

Cece’s initial seizure occurred when she was approximately 4 to 5 months old. She received her routine childhood immunizations earlier in the day without incident. Later that evening, the child’s mother, Cheyanne Clevenger, noted that one of Cece’s arms was moving repetitively.

She contacted her mother, Kendra, and was advised to summon an emergency squad due to a possible seizure. By the time the EMS personnel arrived, the infant was exhibiting no unusual problems, and Mulholland said the mother was advised that the infant did not appear to need treatment.

Later that night, Cece’s infant alarm triggered that the baby’s heart rate was greater than 200 beats per minute. Clevenger immediately checked on the infant and found her having a grand mal seizure. She was transported to a local hospital and then transferred to a hospital in Toledo, where Mulholland reported lab tests and an electroencephalogram, a record of her brain activity, were all normal.

While some individuals have attempted to link the diagnosis of Dravet Syndrome with immunizations, it is believed that vaccine-induced fever is likely the trigger for the seizures. It is possible that vaccination might trigger earlier onset of Dravet Syndrome in children who, because of an SCN1A mutation, are destined to develop the disease regardless of vaccination status, according to a paper in The Lancet Neurology journal.

More seizures

Following Cece’s first seizure, Mulholland said they noted a pattern of the seizures, with one often occurring the first week of every month. Another grand mal seizure occurred when Cece was 10 months old. That seizure lasted for 55 minutes and required such heavy sedation that the infant had to be placed on a ventilator until the seizure could be managed.

Mulholland said the family maintained oral airways, suction canisters, oxygen concentrators and SAMI cameras in their homes, in an effort to quickly identify and treat Cece’s seizures. They maintained “rescue medications,” to enable her to receive prompt treatment.

While some might consider her a “special needs” child, Mulholland said, “She was not special needs to us, but simply special.”

The final seizure

Cece had her final seizure on June 15, 2022. Although she was transported to a local emergency room, where valiant efforts were made to resuscitate her, Cece left the family that loved her so much.

Mulholland describes that as “the worst day of my life.”

Although he attempted to prepare himself after receiving a text from his wife telling him that CPR was in progress, the dreaded reality began “when the doctor and nurse came in and shut the door (of the family consultation room).”

The first poem

Following Cece’s death, Mulholland returned home to find reminders of Cece throughout their home.

“Her toys were on the deck,” he said. “I opened the door from the garage leading into the kitchen, and the first thing I saw was her high chair staring at me.”

The day following Cece’s death, as Mulholland wondered how to survive this tragedy, he began writing poetry. His first poem, “Poppy’s Little Girl,” describes a “warrior intense” with “beautiful blue” eyes and “curls.”

After the initial poem on June 16th, Mulholland began to write a poem every Wednesday following Cece’s death. He viewed the poems as a way to honor Cece. He began posting the poems on Facebook, where his friends suggested they should be compiled into a book.

Last Wednesday

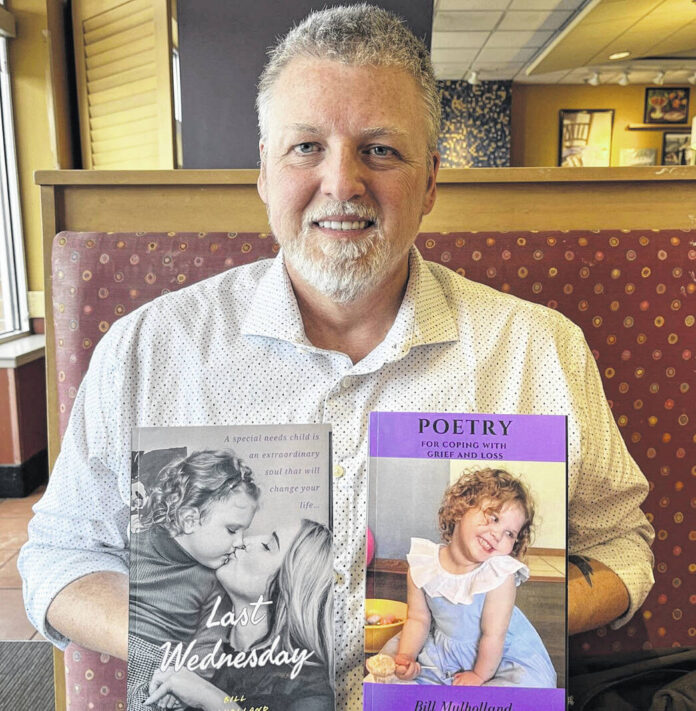

Once Mulholland completed and published the book of poetry in early February, he wrote his second book in 20 days. That book, “Last Wednesday,” features Cheyanne and Cece on the cover and chronicles the family’s journey caring for a special needs child through grieving the loss of that child.

Mulholland is currently working on his third book, “Why Am I Here?” He admits to some significant self-reflection over the past year. He wants to understand for himself, and to help others understand, “God’s purpose for your life.”

Mulholland’s books are sold on Amazon. His poetry anthology can be accessed free-of-charge on Kindle Unlimited. Readers can learn more about Mulholland on his website, billmulholland-author.com.

Her reality

Mulholland has many favorite photos and videos of his blue-eyed granddaughter with the blonde curls and the infectious laugh.

The photo that helps him get through each day is the one given to the family by a friend following Cece’s death. The photo depicts a smiling Cece being embraced by a loving Jesus.

“I look at that picture every day,” Mulholland said, “and I tell myself, ‘That is her reality.’ That is what gets me through each day.”

Reach Brenda Keller at [email protected].