ST. LOUIS — In some small parts of Antarctica, you can lay a sandwich down on the ground and return to it a month later, and it will be fine to eat.

The McMurdo Dry Valleys of Antarctica are perhaps the driest places on Earth; protected by mountains, they see virtually no precipitation, ever. The snow that happens to blow there quickly evaporates. And it’s too cold for bacteria to survive. Basically, there is no way for food to spoil.

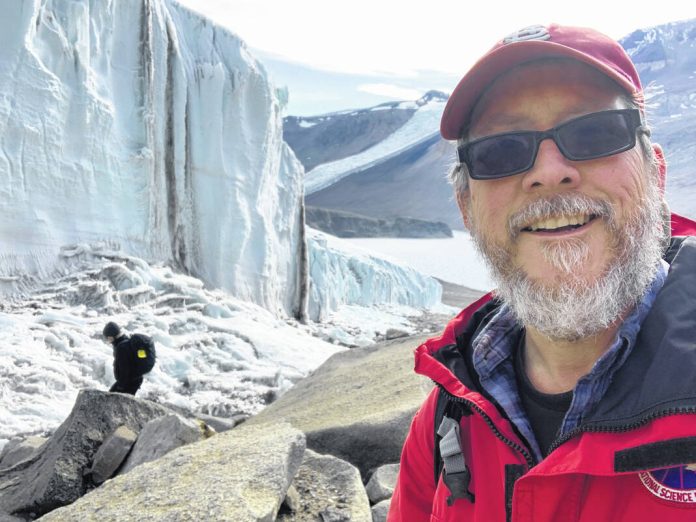

Maplewood-Richmond Heights (Missouri) Middle School science teacher Bill Henske spent a couple of months in Antarctica a year ago; he participated in a long-term ecological research project that is examining changes in life forms in the exposed soil, primarily microorganisms that live inside rocks.

Some of these organisms are dormant for years or decades at a time. When the circumstances are right, they are active for a short time, and then go dormant again. No one knows for sure, but they may be centuries old.

Henske was at McMurdo from December into February, which is to say the dead of summer. The sun never set; it was daylight the whole time he was there. Temperatures ranged from about 10 to 30 degrees, but never stayed warm enough for long enough for bacteria to thrive, at least on the surface.

Seals and sometimes penguins get lost and head inland by mistake. When they die, their bodies do not decompose, Henske said. They turn into mummies. They last until grit in the wind erodes them away.

Built as a Naval base, McMurdo Station is now a community of scientists, run by the National Science Foundation. About 1,200 people live and work there, in dormitory-style buildings. They eat at a galley, which Henske said is “kind of like a college dining hall, where they have pasta stations and they have a salad bar, they have a big dessert bar.”

The residents eat well, or at least eat a lot — their work expends a lot of calories. But there are limits to what they can eat.

It is too expensive to have food flown in on the helicopters that are reserved for people only. All the food is brought in a couple of times a year, on a single cargo ship that follows an ice breaker into the harbor.

The week that the ship is there, the station’s two bars (Gallagher’s and Southern Exposure) are closed. Apparently, Henske said, things would get too rowdy with the sailors in town.

But it wasn’t just the sailors. In October, the bars stopped selling alcoholic drinks altogether, in the wake of persistent complaints of sexual harassment and assault. Alcohol is now rationed out in bottles only.

Based in New Zealand, the ship brings what it can, but that largely means food that is frozen or canned. No fresh fruit or vegetables.

So the salad bar had no lettuce, but a selection of things like slaw and rice-based salads and kimchee. Sometimes, they would offer an entire bar of things that have been pickled.

“Sunday brunch was like an all-you-can-eat buffet, with a carving station. It was usually pretty edible,” Henske said.

Though the residents are restricted by weight in how much clothes and gear they can bring with them, some choose to carry as many pounds of fresh fruit or vegetables as they can. This they then use for barter.

“When some people get an avocado, they would just walk around and hold it, so everyone can see they have an avocado,” he said.

The cooking staff was proud of what they made, he said, everything from chicken-fried steak to taco night to a potato bar, plus pizza every day. They always offered at least four kinds of fresh-baked cookies, and pies and cakes in “flavor combinations I’d never imagine, made with whatever ingredients they happened to have.”

Because the sun shines all day long in the summer, and not at all in the winter, the station operates in shifts, 24 hours a day. For the sake of the kitchen staff, meals were scheduled at the same time: When the day shift was having its breakfast, the night shift would eat their dinner. Those coming in for dinner always received their food first, Henske said — “That was sacrosanct.”

When the meals were not being served, the galley was always open for coffee or popcorn or snacks. Snacks were always very popular. And residents sometimes took advantage of the unusual climate conditions.

“A lot of the food is 10 to 15 years past the expiration date. Some grad students and I would play a game — we would look for the oldest food and eat it,” he said.

“The dry goods, the canned goods, will sit there forever. Some things you think are shelf-stable aren’t 10-years shelf stable, like Slim Jims.”