Dick Bramer, 76, likes to watch birds flock outside the window of his home in Scandia. But for two years he couldn’t see them well enough to identify the various species.

In July 2021 Bramer suffered what doctors diagnosed as an ocular stroke (they said a small particle of plaque must have blocked blood flow to the optic nerve) in one eye. He already had lost vision in his other eye decades earlier, due to what doctors said was a swollen optic nerve.

After the stroke, everything was blurry. When he watched a football game, his wife, Polly, had to tell him the score and the time left, because he couldn’t see the writing on the TV screen. He couldn’t safely do the woodworking projects he used to love. When they went to see their grandchildren play football, soccer or baseball, he couldn’t follow the games because he couldn’t see the ball.

The Bramers looked everywhere for something that might help. They went to stores catering to low-vision consumers, but found that most of the products were aids to help people function better without their vision, not improve its clarity.

Then a friend happened to tell them about Low Vision Restoration in Blaine, Minnesota. Optometrist Chris Palmer, who founded the clinic, prescribes devices that can help improve people’s vision when other glasses can’t. Palmer fitted Bramer with the devices, which are like miniature binoculars or telescopes affixed to regular glasses.

Bramer tried them out and suddenly saw his wife clearly for the first time since the stroke.

“He said, ‘I can see her! I can see her face! She’s wearing a necklace!’” Polly recalled.

The devices, called bioptic telescopic glasses, can help patients resume reading, recognizing faces across a room, watching TV, playing cards, in some cases even driving, Palmer said. But for reasons nobody seems to be able to explain, few people have heard of them.

“They tend not to be widely utilized, unfortunately,” said Coon Rapids ophthalmologist Scott Peterson, who does refer patients to Palmer. “Some people don’t know that practitioners like Dr. Palmer exist, or they have a hard time finding them.”

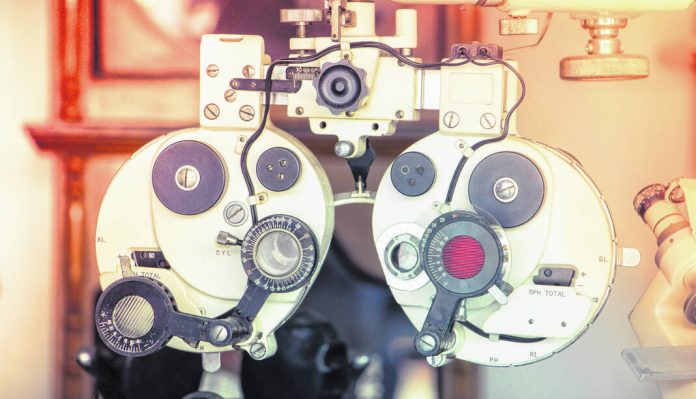

Telescopic glasses are “basically binoculars” that affix to glasses and magnify images so that objects look bigger, closer and clearer, said Palmer, who has specialized in this area since 2008. They resemble jewelers’ loupes.

“It’s like having a miniaturized telescope or binocular stuck right into a pair of glasses,” Palmer said. “They’re two individual eyepieces that you’re looking through.” Their positioning can be adjusted as needed.

Bioptic telescopes are helpful for people with eye conditions — including macular degeneration, ocular albinism, Stargardt disease, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy and rod cone dystrophy — that can reduce vision to levels too low to benefit from regular glasses and contacts.

The devices won’t help everybody with eye problems, Peterson noted, “but in many cases people can regain some level of independence, reading, the ability to perform tasks around the home,” he said.

Another reason they’re not more widely used is that they’re expensive and generally not covered by insurance, Palmer said. Then again, hearing aids — an analogous product in many ways — can be expensive and often aren’t covered, either, but most people know about them.