What an extraordinary life John Lewis lived. And how much he gave to us all.

Anyone with a sense of American history knows the highlights. Lewis was born in 1940 as one of 10 children of Alabama sharecroppers and rose to become an icon of the Civil Rights Movement and a lion of the U.S. Congress, exemplifying the phrase that became his motto: “good trouble.”

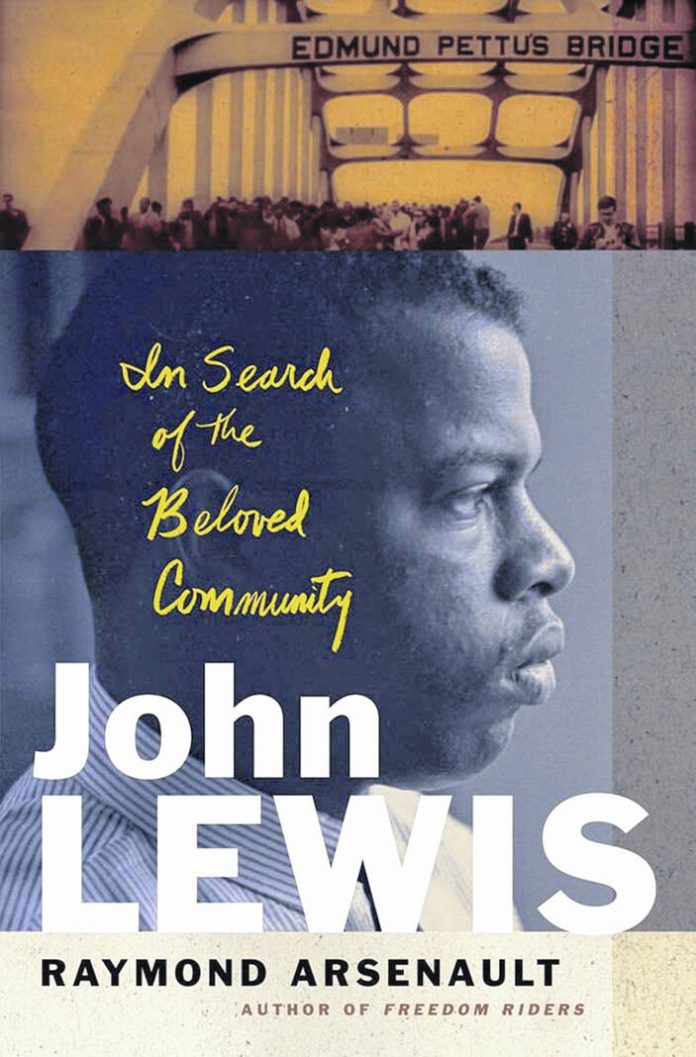

With “John Lewis: In Search of the Beloved Community,” Raymond Arsenault gives us not only the first full biography of the man — Lewis died in 2020 — but a deeply researched history of the movement that he led and served all his life, a movement that is an essential chapter in American history.

Arsenault is the University of South Florida’s John Hope Franklin professor of Southern history emeritus and the author of several other books, including “Arthur Ashe: A Life.”

Arsenault met Lewis in 2000, as he was researching his 2006 book “Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice.” (That book became the source for an Emmy-winning PBS documentary and an opera.)

In this book’s preface, Arsenault notes his friendship with and admiration for Lewis. “My intention throughout,” he writes, “has been to avoid hagiography and hero worship, telling Lewis’s full story with all its ups and downs intact.” That he does.

Even as a child, Lewis knew he wanted to move beyond his tiny hometown of Carter’s Quarters, Alabama: “Early on, not long after he was given his first Bible at the age of 4, he decided he wanted to become a pastor.” (Arsenault notes the first audience for his preaching was the family chickens.) He loved school and read voraciously, but he was sharply aware of the differences in the segregated school system, like the tattered, hand-me-down books and rusty school buses for Black children.

The Brown v Board of Education decision in 1954 seemed a ray of hope to the boy, but the immediate, violent white backlash to it all over the South cast a pall of fear. Then in 1955, Arsenault writes, Lewis experienced a “spiritual awakening” when he heard a radio sermon by Martin Luther King Jr.

It was the teenage Lewis’ first exposure to the concepts that would shape and sustain him: social justice Christianity, Gandhian nonviolence and the Beloved Community, “a society of equity and justice freed from the deep wounds inflicted by centuries of exclusion, prejudice, and discrimination.”

Lewis was active in civil rights demonstrations and had met King and other leaders. He impressed them with his sense of purpose and his courage, and he soon moved into leadership roles himself, first in lunch counter sit-ins and then, at barely 21, as one of the Freedom Riders who defied violent attacks to desegregate public transport in the Deep South in 1961.

In 1963, he would be named chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and speak before a quarter of a million people at the March on Washington, followed by King’s legendary “I Have a Dream” speech. In 1965, Lewis led a voting rights march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, on what came to be called Bloody Sunday. Photos of the ferocious police response to the nonviolent march, including one of Lewis beaten to the ground by a white officer, shocked the world. Diagnosed with a fractured skull, Lewis nevertheless was out of the hospital and back at work days later.

But Arsenault takes us beyond those media moments. He recounts in careful detail the enormous amount of planning, training and cooperation those demonstrations required. Participants were not only educated in the principals of nonviolent resistance but went through role-playing exercises to learn how to withstand the worst insults and attacks without succumbing to rage. Lewis himself was jailed dozens of times and beaten more times than that, yet did not retaliate. Throughout his life, people responded to his gentle demeanor and forgiving nature.