Like any great rivalry, the competition and, later, the lucrative partnership between Chicago Tribune film critic Gene Siskel and Chicago Sun-Times film critic Roger Ebert has been dissected and debated a lot over the past few decades, nowhere more avidly than in the city they called home.

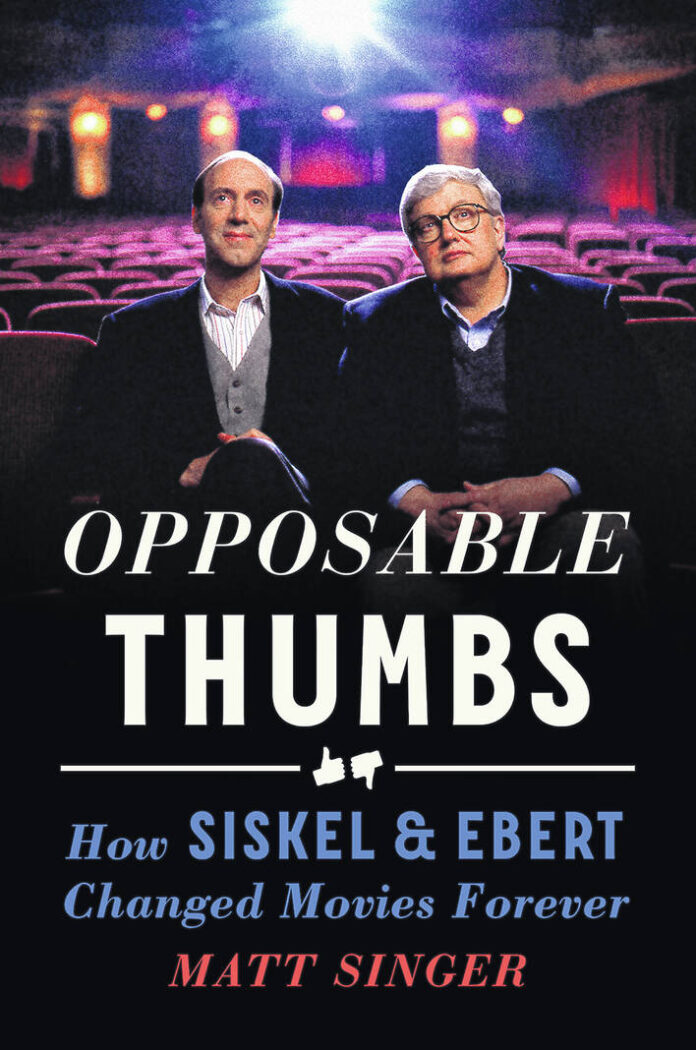

The book “Opposable Thumbs: How Siskel & Ebert Changed Movies Forever” was released Oct. 24. It’s a sharp-witted account of how these two neatly contrasting Chicago media paragons no longer with us — Siskel died of a brain tumor in 1999 at age 53; Ebert died at age 70 of thyroid cancer in 2013 — learned how to argue about movies on TV and made a few million in the process.

The author is Matt Singer, a critic, journalist, author and longtime “obsessive Siskel and Ebert fan” (his words) best known as editor of the screencrush.com website. If you watched the final iteration of the movie review program, “Ebert Presents: At the Movies,” which ran 2010-2011 on PBS stations, you may recognize Singer as a segment contributor.

That’s his first-hand experience with the Ebert universe. Here’s mine: In 2007 I filled in, off and on, opposite co-host Richard Roeper after Ebert got sick. Later I did a few months straight with Roeper and then co-hosted with A.O. Scott (then a chief film critic of the New York Times) for the final season, 2009-2010.

Two middle-aged white guys, in sweaters, disagreeing even in agreement on a film: How Siskel and Ebert parlayed that formula into international stardom, with regular appearances on Letterman, Leno and beyond — it’s a good story, told adroitly and often movingly by Singer.

Q: Where did it start for you with these guys?

A: When I was 14, summer of 1995. One show that summer, they talked about “Trainspotting,” and in Providence, Rhode Island — I grew up in suburban New Jersey — there was a theater showing Danny Boyle’s film. I shouldn’t have been allowed in; I was the smallest 14-year-old that ever existed. But I was and it blew my mind, and I have Siskel and Ebert to thank for it. By that time I’d probably been watching the show since I was 12.

Q: Let’s go back, as you do in your book, to how they got to their respective papers in the beginning. Ebert’s working on his doctorate at the University of Chicago and needed a job. Herman Kogan of the Chicago Daily News published a couple of Ebert freelance pieces. Impressed, Kogan arranges a lunch for Roger and two editors over at the Sun-Times. The job offer with the Sun-Times Sunday magazine section arrives even before they get the dessert order in. This was in 1966 and Roger’s made film critic the following year.

Two years later, Siskel’s at the Tribune and film critic Clifford Terry goes on a year-long leave for a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard, and Gene makes his move. So you have these two fiercely competitive writers, Ebert and Siskel, who at the time hardly knew each other and rarely spoke to one another. When you watch the very first episode of their first venture, “Opening Soon at a Theater Near You” produced by WTTW-FM for public TV, you don’t get a lot of the competitive juice, do you?

A: It’s striking how little you get. In the beginning, in 1975, they authentically didn’t like each other yet, but it actually doesn’t come across that way on TV because it’s pure discomfort. Fascinating dichotomy. What you see (in the pilot) is what the Siskel and Ebert imitators later were like, some of them, anyway.

It was (WTTW producer) Thea Flaum who saw it through, kept them around and together, saw the potential — and figured out how to bring their off-camera energy, so combative and combustible, to what they could do on-camera. Both men always said she was the one who figured it out.

Q: Your subtitle, “How Siskel & Ebert Changed Movies Forever,” is a bold assertion. Talk to us a little more about that.

A: It is a bold assertion. But I think their influence and importance looms large. Certainly they influenced the way we talk about movies even today. When they made it on TV, they used their megaphones for the good of the movies, and for a force for change. In 1990, I think it was, Entertainment Weekly had their 100-most-powerful-people-in-Hollywood issue. And Siskel and Ebert landed at No. 10, behind Michael Eisner (then CEO of the Walt Disney Company which owned the show in its most popular stretch). Behind Eisner, but ahead of Jeffrey Katzenberg (then chairman of Walt Disney Studios), their boss, more or less at Disney at the time.