Stephen King does something amazing in his new novel, “Holly,” that you might not even notice at first.

It’s not that “Holly,” unlike most of his other 65 novels (not counting collaborations and those written under another name), has no supernatural elements. It’s a realistic mystery rather than a horror story or fantasy.

What’s amazing is that it’s a mystery in which he shows the reader who the criminals are, how they commit their dreadful crimes and why, from the early pages of the book. The reader is, at almost every turn, way ahead of the detective, beloved King character Holly Gibney, veteran of four other novels (the “Mr. Mercedes” trilogy and “The Outsider”) plus a novella, “If It Bleeds.”

How do you create and maintain intense suspense when you build a story that way? Let King show you.

King fans first encountered Holly as a minor character in “Mr. Mercedes,” and her association with retired cop-turned-private-investigator Bill Hodges as they battled a monstrous killer across three novels became both a deep friendship and a business partnership.

Holly started out as an introvert struggling with anxiety and OCD. She had few social skills and no self-confidence, but was gifted with sharp observational sense and logic. Over several books she’s blossomed ― to a degree.

After Bill died of pancreatic cancer, Holly came to rely on her new business partner, another ex-cop named Pete Huntley, and teenage siblings Jerome and Barbara Robinson, whose digital skills and big-hearted courage have been essential to her.

After a prologue set in 2012, “Holly” begins in July of 2021. That was, you’ll recall, not long after COVID-19 vaccines became available, and King makes that part of his story, along with the aftermath of the insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021, and the Black Lives Matter movement.

We learn that Holly’s domineering mother, Charlotte, was an anti-vaxxer and has recently died from COVID, protesting to the end (from her hospital bed) that the virus is a hoax. Holly is grieving and furious, and she’ll soon find out she has a lot more reasons to be angry at her mother — about 6 million of them.

Pete has COVID, but a mild case (he says), and Jerome and Barbara are busy with writing projects, so Holly is working alone, although not much is going on for Finders Keepers, her business.

Then she is hired by Penelope Dahl, who wants Holly to find her daughter, Bonnie.

Bonnie Rae Dahl is an adult and has only been missing for a few weeks, so the police are lukewarm about the case. But Penny insists Bonnie wouldn’t disappear without a word, and Holly is inclined to believe her.

Bonnie left her job at the library of Bell College, a local liberal arts school, on her bike. She stopped at a convenience store where she was a regular customer, bought a soda and chatted with the cashier — all of this caught on video — then rode away. Her bike was found in a scruffy part of town with an ambiguous note on the seat: “I’ve had enough.” She hasn’t been seen since.

So Holly gets to work, methodically pulling threads that might lead to Bonnie. At one point, there’s a shout-out to one of her role models: “Holly is a fan of Michael Connelly’s detective hero, Harry Bosch, and especially of Bosch’s number one maxim: get off your ass and go knock on doors.”

As she keeps knocking, she keeps finding threads that lead to other missing people: a skater boy last seen at the local Dairy Whip and a young Black lesbian who also worked at Bell College (those two vanished within days of each other in 2018) and a gay Hispanic novelist who was a visiting writer at Bell when he disappeared almost 10 years ago.

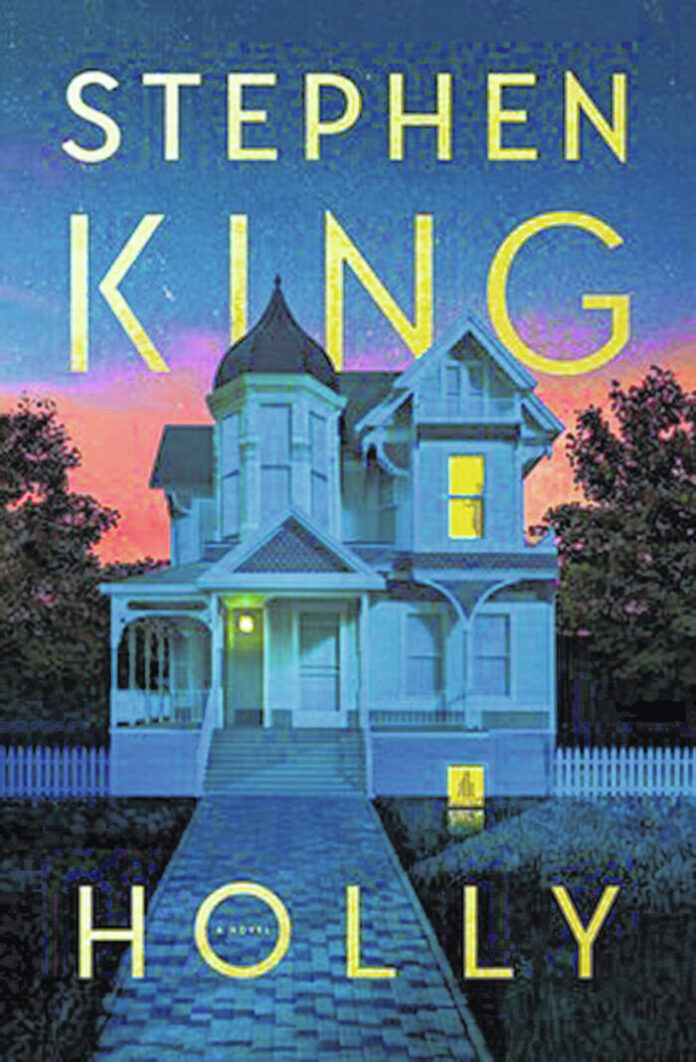

As Holly wonders whether there’s a connection among them, the reader meets Emily and Rodney Harris. The long-married couple, both retired from Bell, live in a charming Victorian house near the town’s sweeping park. Emily taught English and belies the notion that all college professors are “woke” — she’s as viciously racist and homophobic as they come. Rodney has his own obsession: diet. A biologist and nutritionist, he earned the nickname “Mr. Meat” from students for his classroom diatribes about what humans should eat.

The Harrises are old and getting older, and Rodney’s beliefs about what they must eat to stay healthy and stave off aging have taken a very dark turn.

One of the strongest elements of King’s fiction has always been his placement of his horrors solidly in the real world, putting them that much closer to us. Much of “Holly” is built upon that. King is 75 himself, and his depictions of Emily’s excruciating sciatica and Rodney’s severe arthritis and creeping mental deficiency are vividly believable.

King’s own storytelling skills are not dimming one bit. The structure of the novel expertly brings Holly’s quest and the Harrises’ desperate crimes ever closer without either side being fully aware of each other until it’s too late.

The reader, though, knows all. It’s a lot like watching a scary movie and hollering at the good guy, “No! Don’t go in the basement!”

Really, don’t go in the basement. And don’t look in the refrigerator, either.