Over his long life, Wendell Berry, now 88, has composed a steady stream of remarkable essays, novels and poems celebrating traditional American agrarian practices and communities and lamenting the industrialization of agriculture, the foul ubiquity of pollution, and the rise of the churning, impersonal global economy.

Heavy stuff, all that. And some critics, reasonably enough, have suggested that his nostalgia for simpler times is naïve, overly romantic.

That’s a long, fraught discussion. But all can agree on this: Wendell Berry is an American literary treasure.

Most casual readers know Berry best by his exquisite poetry, especially “The Peace of Wild Things,” or by the passionate essays in which he has argued his causes. Less well known are his novels, set in fictional Port William, Ky. (Berry himself is a longtime Kentucky farmer.) The novels chronicle the lives of several generations of rural farmers, celebrate their connections to the land and each other, and acknowledge that world’s slow fade.

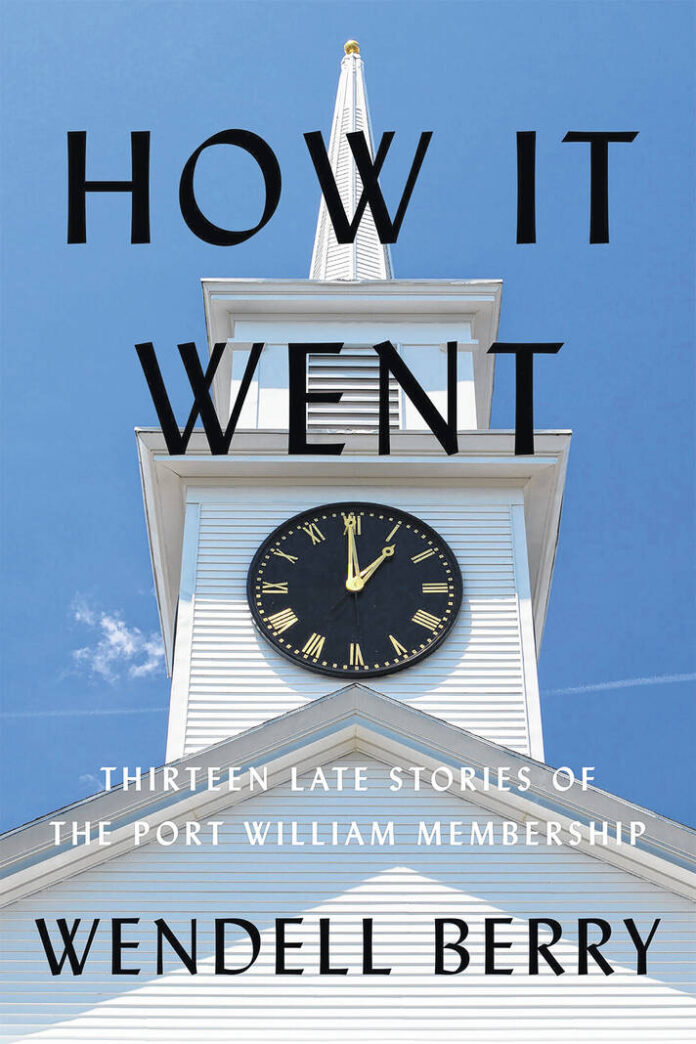

“How It Went,” Berry’s 14th Port William novel, consists of 13 memories of Andy Catlett, one of Berry’s recurring characters. It opens on Aug. 15, 1945, as young Andy joyfully clangs a bell in honor of V-J Day.

“Ring the old bell, young Andy Catlett,” Berry writes. “Ring your ignorant greeting to the new world of machines, chemicals, and fire. Ring the dinner bell that soon will be inaudible at dinnertime above the noise of machines. Ring farewell to your creaturely world, to the clean springs and streams of your childhood, farewell to the war that will keep on coming back.”

By mid-book, middle-aged Andy is scarred in many ways, including by the loss of his right hand to a clogged corn picker. “The machine had taken his hand, or accepted it, as the price of admission into the rapidly mechanizing world that as a child he had not foreseen and as a man did not like, but which he would have to live in, understanding it and resisting it the best he could, for the rest of his life,” Berry writes.

At book’s end, Andy, having “passed the watershed in his life when he began losing old friends faster than he made new ones,” is mournfully recalling long-dead neighbors and the way of life that vanished with them.

A misty melancholy hangs over every page of this novel. But Berry’s powers as a writer render that heartbroken tone beautiful.

Berry is a master craftsman in all literary genres. No extra word or shabby sentence mars his work. The reader pauses often to admire the crystalline precision of his writing.

Despite its elegiac tone, “How It Went” is not despairing, and neither, we hope, is Berry. Many Americans share his sense that traditional farming practices nurture both people and land, and that we must slow down and listen to each other in order to nourish what is best about America.

Let us hope we also can embrace Berry’s quiet celebration in this work and others of how people can learn to get along when they share a community. Though he writes almost exclusively of times past, Berry is a powerful writer for our time.