Two and a half weeks before marching bands, a stunt pilot and “Diablo the Human Torch” entertained some 50,000 people at the dedication of Schoonover Park, the man most responsible for making it all possible quietly tried out the park’s recently completed swimming pool.

“T.R. Schoonover, president of The City Loan and Savings Co., and donor of Schoonover Park to the city, Sunday had the honor of taking the first ‘dip’ in the park’s new $140,000 swimming pool,” The Lima News wrote June 17, 1940.

“Taking advantage of the first water test at the pool, the philanthropist, members of his family and a few friends staged an informal initiation of the new swimming plant which will become the mecca for thousands of Lima and district bathers on and after the big Fourth of July dedicatory celebration. Splashing into the pool’s clear waters with the enthusiasm of nine-year-old boy, Schoonover proudly waved to the small audience which stood by to witness the first plunge,” the newspaper added.

The wear and tear of 80 years, however, took a toll, and at the end of summer in 2019 the last of those tens of thousands of swimmers The Lima News foresaw flocking to the pool clambered out of it.

Lima had long wanted a public swimming pool, and the topic came up again on a hot July day in the middle of the Great Depression.

“Plans for a swimming pool estimated to cost $55,000 and capable of accommodating as many as 25,000 persons daily were disclosed at a meeting of Lima playground officials, city and federal authorities Tuesday night in the office of Fred L. Roose, Work Progress head from the 13th district,” The Lima News reported July 22, 1936. The Works Progress Administration was a federally funded jobs program.

As a result of the meeting, a committee was formed, an executive board organized and a slogan contest declared. An expert from Terre Haute, Indiana, told the meeting of “the present trend toward artificial bathing facilities under competent supervision.”

In late October 1937, the dream came within reach.

“In a few simple, unassuming phrases, Thomas R. Schoonover, donor of McCullough’s park to the city of Lima, turned over the deed to the property to the city at a program staged in Central High School,” the News reported Oct. 28, 1937. The newspaper noted that the property had been purchased by Schoonover at a price “reported in excess of $25,000,” and “has been designated as Schoonover Park by act of city council.”

McCullough Park once had a large swimming hole, Ferris wheel, merry-go-round, penny arcade, fun house, roller coaster “and the finest dance hall in this part of the state” and was known as Lima’s “playground of the Twenties,” a former manager of the park told the Lima Citizen in May 1959. By the mid-1930s, however, the park had become rundown and was sold to Schoonover.

Schoonover, in addition to donating the park to the city, pledged “$25,000 to improve the resort and $5,000 annually for 10 years for its upkeep.” He would ultimately give much more, in land and money.

On Jan. 2, 1938, The Lima News revealed plans for the park to be funded, “in addition to the sizeable cash donations from Schoonover,” by a “vast sum” from the federal government assured by its inclusion as a WPA project.

“Among the major projects planned for the park are an elaborate swimming pool, wading pool, a spacious auditorium, shelter houses, a club house, recreation grounds, tennis courts and other recreation facilities including a club house, a boat house and other features,” The Lima News wrote, adding that 125 WPA workers were “engaged in preliminary cleanup work at the park site.”

On Feb. 22, 1938, The Lima News announced that the pool, “one of the biggest features of Lima’s newest recreation center,” would cost “in the neighborhood of $121,000” and that construction of the “elaborate WPA project” would begin in two or three weeks and employ 200 workers for eight months.

The estimated start of construction was optimistic, as was the pool’s price tag. On June 5, 1938, The Lima News took another stab at it, announcing that “preliminary work” on “the most inviting and modern plant of its kind in this part of the state” would begin in the coming week. The pool, the newspaper reported, would cost $140,000.

Nearly a year later, on May 28, 1939, The Lima News reported work would start that week on the 100-by-220-foot pool, which would accommodate 1,200 bathers, on the high ground along Findlay Road on the northeast side of the 41-acre park. That ground, like the park itself, had been donated by Schoonover, who purchased the four acres for $3,500 in October 1938.

The Lima News noted that the site was “ideal for swimming pool purposes, affording much better drainage than the park’s old swimming pool site of McCullough’s Park days.” Johnson’s Swim, as the old site was known, was in the southwest part of McCullough’s Park, off Jefferson Street.

Finally, in early May 1940, the city announced that Schoonover Park would be dedicated on the Fourth of July. On May 17, 1940, in an open letter, The Lima News declared, “It is appropriate that the dedication celebration should be held on this day. It affords all Lima a splendid opportunity to turn out by the thousands in tribute to the city’s No. 1 citizen, T.R. Schoonover, the park’s donor.”

And turn out they did, although whether it was to honor Schoonover or enjoy the entertainment — including “Diablo,” a Lima man who dove off a 75-foot tower into flame-covered Schoonover Lake — is uncertain.

“Formal presentation of Schoonover Park to the city marked Thursday’s dedicatory festivities attended by some 50,000 persons,” The Lima News wrote July 5, 1940. “The Fourth of July ceremonies also featured an all-day program of sports events, swimming in the $140,000 pool and an elaborate display of fireworks in the evening.”

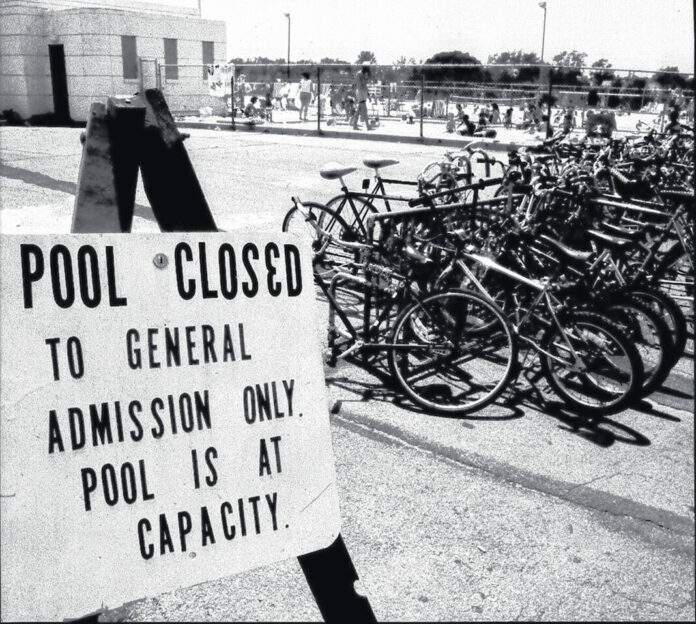

For the next eight decades, through wars, riots and the mid-60s threat of topless swimwear for women — which briefly fretted over by city council in 1964 and fervently hoped for by adolescent boys, never reached Lima or much of anywhere else — Memorial Day meant Lima’s public pool was about to open.

Although cosmetic improvements were made to the pool over the years — a sunbathing area in 1959, a water slide in 1994 — it began to show its age. By 2011, city officials were floating the idea of closing the pool to save the city about $30,000 per year.

By 2019, the pool was leaking roughly 9 million gallons of water every season and had become a financial drain on the city as well. The coronavirus kept the pool closed in the summer of 2020, while an inspection by the city that September found, according to The Lima News, that “the pool is in an unacceptable state to open for the 2021 season.”

After discovering the cost of repairing the pool would top $1 million, the city decided to replace it and recently unveiled plans for a new public pool between Spartan Stadium and Lincoln Park.

SOURCE

This feature is a cooperative effort between the newspaper and the Allen County Museum and Historical Society.

LEARN MORE

See past Reminisce stories at limaohio.com/tag/reminisce

Reach Greg Hoersten at [email protected].