Lee Cary was a 20-year-old sailor a long way from home when he witnessed the beginning of a terrifying new chapter in the Cold War.

On Nov. 1, 1952, Cary was on a ship in a U.S. Navy task force a little more than 30 miles away from Eniwetok Atoll in the South Pacific when the U.S. conducted the first full-scale test of a thermonuclear device. Cary described the blast, which he called “even close to being beautiful,” in a letter to his family in Lima.

In the charged atmosphere of the Cold War, Cary’s letter as well as similar letters from other sailors who were there resulted in threats of prosecution and punishment.

Within 10 days of the Eniwetok test, Cary’s letter had arrived in Lima, and his mother, Mary Spahr Cary, was sharing it with some customers at the family’s grocery store on the corner of North and Baxter streets. One of those customers was a Lima News editor who, according to Cary’s sister, Connie Lowry, frequently shopped at the store.

“Because mother knew him, she felt it was okay to show him the letter,” said Lowry, who was about 12 years old at the time. “She didn’t expect it to be published.”

It was.

Under the headline “Hell-Blast Described,” The Lima News published the letter, though not naming its author, on the front page of the Nov. 10, 1952, edition of the newspaper.

“Although the eyewitness did not identify the type of bomb exploded, there is a growing belief throughout this country that the explosion he saw was America’s first experiment with a hydrogen bomb,” the newspaper wrote.

In the letter, Cary chronicled his day from ship’s crew muster at 6 a.m. until “shot time” at 7:15 a.m. The minutes were counted off beginning at 7:05 a.m.

“We were told where the explosion was to be, and we were to turn away from this point and cover our eyes with our arms. Ten seconds after the shot, we would be able to look with no damage to our eyes,” he wrote.

“0715 SHOT TIME,” Cary wrote. “We didn’t know the explosion had taken place yet, but within five seconds we felt a heat wave hit our backs, and it was hot – about 180 degrees when it hit us and we were 30.4 miles away from dead center! Thirteen seconds after shot time I looked up – I could hardly believe my eyes, a flame about 2 miles wide was shooting 5 miles into the air. This lasted for about 7 to 10 seconds. Then we saw thousands of tons of earth being drawn straight into the sky. Then the cloud began to form, about 20 seconds after the shot. We heard the sound of the explosion, and even at 30.4 miles away it made my ears ring! Now the mushroom had taken place and shape. It was about a mile wide at the bottom, and it was at least 20 miles wide at the top.”

In a story accompanying Cary’s letter, The Lima News staff writer John Mitchell noted that he had witnessed an atomic bomb test in 1946 while he was a crew member on a submarine that was part of the target fleet at Bikini Atoll in the South Pacific during atomic bomb tests there.

“The bomb I saw go off six years ago was an atomic pea shooter!” Mitchell wrote. “That is apparent after reading the letter of the Lima resident who has written home describing the latest major nuclear weapons tested at Eniwetok.”

Mitchell ended by noting that what he witnessed a half dozen years earlier now “ranks as a minor weapon in the atomic collection. I hope I never see a major one.”

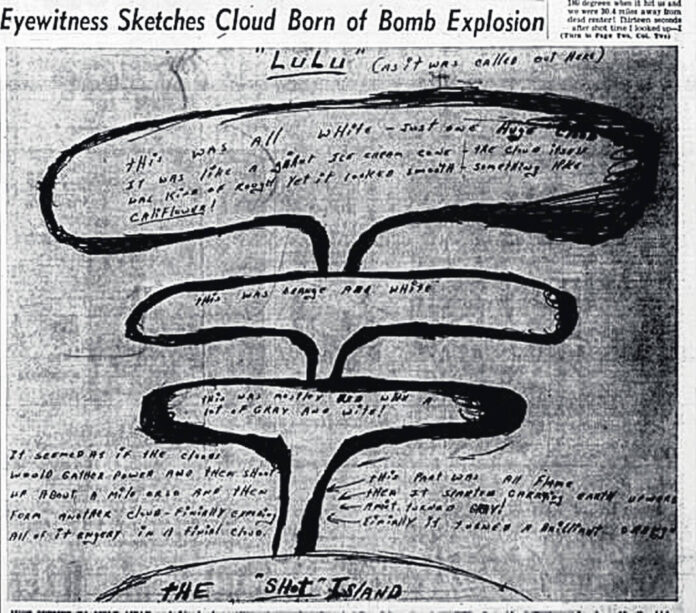

In concluding his letter, which would appear in newspapers nationwide and as far away as Guam, Cary wrote, “I guess I have about told all I can. I’m going to draw a picture so it may help you some!”

To government officials, Cary had told much more than he should have.

By Nov. 17, a week after The Lima News published Cary’s letter, officials were confirming that the “super explosion” at Eniwetok was, indeed, a hydrogen bomb. The Lima News proclaimed that the announcement confirmed its “copyright story based on a graphic eyewitness report written to his family by a Limaland resident serving with the test fleet at Eniwetok atoll.”

The wire report, however, also hinted at the worrisome possibility of punishment for those who wrote such letters.

“The Justice department was reported to be looking into the matter of the H-bomb letters,” the wire service reported, adding, “Investigations are underway leading to possible disciplinary action or prosecution for violation of task force regulations or the law.”

An Associated Press story from Nov. 16 reported the Atomic Energy Commission “exhibiting alarm about” the reports, disclosed “that the crewmen of ships in the test task force who wrote home about seeing such a superblast face the prospect of prosecution.”

The fear, a follow-story on Nov. 17 explained, was that the “letters, if accurate, contain unintentional tidbits of scientific information of major value in guessing how good the United States’ newest and mightiest weapon might be.”

Connie Lowry said the FBI showed up at the Cary family home in Lima “almost immediately.” The whole affair, she added, worried her mother who “was afraid her son would be put in prison, and it was all her fault.”

In the days following the threats of punishment against the H-bomb letter writers, newspapers nationwide noted that, though the letters might have violated the spirit of task force regulations, there had been no censorship. Besides, keeping a massive explosion secret was probably impossible.

“The fact is that you can not keep secret an experiment which employs a great number of men,” the International News Service wrote Nov. 19. “You can not do it forever, that is. And who knows why these purported ‘leaks’ were allowed. Was it a case of laxity of security or was it done deliberately to impress the Russians?”

Lowry said the investigation seemed to last a long time, and the family never received any indication that “it was either OK or it wasn’t OK.” It just ended, eventually.

Cary served four years in the Navy and returned to Lima, became an ad salesman for The Lima News and, later, the Lima Citizen. He became co-owner of Classic Bowling Supply and owner of C and C Recycling. He was once president of Lost Creek Country Club. In 1955, he married Marilyn Mong, and the couple had two children. He died at the age of 56 on June 10, 1988.

Lowry said she does not know what became of the letter, although she suspects her mother burned it.

SOURCE

This feature is a cooperative effort between the newspaper and the Allen County Museum and Historical Society.

LEARN MORE

See past Reminisce stories at limaohio.com/tag/reminisce

AN EXCERPT

Excerpt from Lee Cary’s letter home describing what he saw Nov. 1, 1952, as a crew member on a U.S. Navy ship some 30 miles off Eniwetok when a thermonuclear device was tested there.

“The actual shape of the rings were oval and the formations of the clouds were like a head of a cauliflower. I said that before. Anyway, the solid part of the mass looked like that! The cloud stayed this shape for about 10 minutes, then it started to break up and dissolve. During this period we could see parts of trees and lots of earth being dropped into the water and back on the island. About 15 minutes after shot time the island on which the bomb had been set off from started to burn, and it turned a brilliant red. It burned for over six hours. During this time it was gradually becoming smaller. Within six hours an island that had once had palm trees and coconuts was now nothing. A mile-wide island had actually disappeared! I was watching thru a pair of binoculars, and at first I didn’t notice, but a hugh (sp) chunk just seemed to melt away, so after that I watched closely! I guess I have told about all I can. I’m going to try to draw a picture so it may help you some. I hope I have made myself clear.”

Reach Greg Hoersten at [email protected].