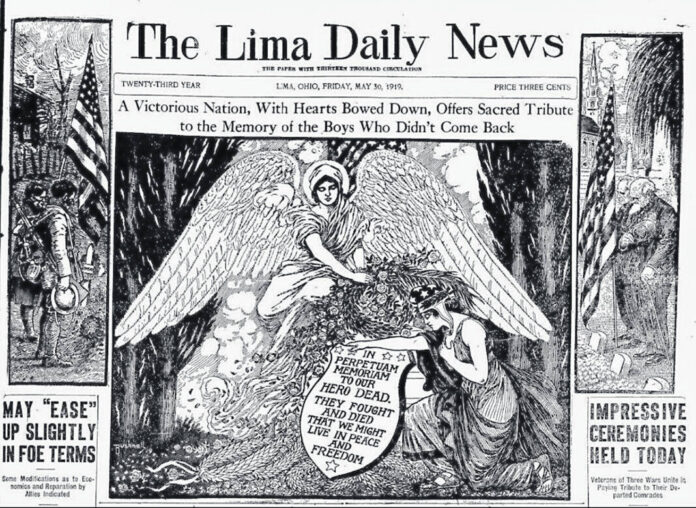

A patriotic front page was on display in the May 30, 1919, edition of the Lima Daily News for Memorial Day. By the time the front page ran, about seven months after the end of World War I, enthusiasm had fizzled for a grand monument to honor the county’s dead from World War I, which was proposed for the center of Lima’s Public Square.

Courtesy of Allen County Historical Society

On Good Friday, April 6, 1917, the day the United States reluctantly entered World War I, Pfc. Charles J. Watson, who had enlisted in the Army at Lima in 1913, was killed in an accident at West Point, N.Y.

Over the next 19 months of war, more than 50 men from Allen County would be killed in combat, while many more would die from disease, notably in the 1918-19 Spanish flu pandemic, or, like Watson, in accidents.

Plans to honor these fallen heroes began in August 1918, about three months before the shooting stopped. Although several memorial groves of trees, plaques and monuments were eventually completed, plans for a monument in Lima faltered as the war and its warriors were seemingly forgotten after the war ended.

On Aug. 31, 1919, the Lima Republican-Gazette wrote that the prevailing sentiment seemed to be: “The war is over. Our boys are dead. Let’s go to the movies,” adding that “plans for a memorial to the city’s soldier dead, eagerly discussed shortly after the armistice, have practically been forgotten now that the majority of the boys who came back are home.”

Twelve years later, however, a monument of sorts was dedicated to the soldiers of and sailors of “the Great War,” and it stands today.

The first of those Allen County boys, bound for mobilization at the state fairgrounds in Columbus, left Lima via the Ohio Electric railway in mid-July 1917.

“Their mothers and sweethearts crowded the interurban station lobby, and there a father could be seen bidding his warrior son goodbye,” the Lima Daily News wrote.

More farewells followed, including the county’s first quota of drafted men in September, and, in October, a contingent of 11 Black men drafted to serve in the segregated U.S. Army. According to the Lima Times-Democrat, 500 people marched in a parade in “beating rain” to see the men off.

Hard on the heels of the farewells, news of the county’s first casualties trickled in. On Oct. 27, 1917, Pvt. Homer D. Herrington, of Lima, who was serving with Canadian troops in the British Expeditionary Force, was killed in action in northern France. By the spring of 1918, the casualty list began to grow faster: Lt. Wellborn S. Priddy, whose father was engaged in the oil business in Lima, died in June 1918 of wounds “somewhere France,” while Petty Officer Oscar Callahan, of Delphos, was lost at sea when the collier U.S.S. Cyclops and her crew of 306 disappeared without a trace in the Atlantic.

Corp. William Paul Gallagher, of Lima, was killed by a shell explosion in June 1918 while erecting barbed wire entanglements near Chateau-Thierry. Lima’s American Legion Post was subsequently named in his honor. Second Lt. Edward J. Veasey Jr. was one of four Lima soldiers to fall in action on the first day of the Battle of the Marne in mid-July 1918, and Lima’s VFW Post 1275 was subsequently named in his honor. And the list grew: Pvt. William S. Lippincott of Allentown, Corp. Clarence Collier of Lima, Pvt. Elmer Harrod of Spencerville, Pvt. George Nolte of Delphos, and on and on.

Many more were dying of disease and accidents far from the front lines. Nurse Lora Gore of Lima died of pneumonia in March 1918 at a camp hospital in San Antonio, Texas. Pvt. Dan Stover, of Cairo, died of pneumonia at camp in Shelby, Mississippi, and the Cairo American Legion Post was named in his honor. Pvt. Joseph Jakutis, who had worked at the Ohio Steel Foundry after arriving in Lima from Lithuania, died in a fall from a hay wagon at Camp Sherman near Chillicothe.

On Aug. 20, 1918, as the British, French and Americans advanced across the Western Front, Lima City Council proposed an oak tree be planted for each fallen county serviceman, with each tree bearing a bronze plate honoring the soldier or sailor.

“Some special street is to be set aside as a Liberty Row, to be lined with the memorials to the dead,” the Republican-Gazette reported. “The entrance to Faurot Park is being considered as a possible site.”

Meanwhile, the number of trees that might be needed for Liberty Row continued to grow. Corp. Glen M. Watkins of Lima was killed on Aug. 21, 1918. Pvt. Walter E. Spees, of Lima, died in September of shrapnel wounds in France while serving with the medical corps. Sgt. Harry J. Reynolds, namesake of the Spencerville American Legion Post, died during the Meuse-Argonne offensive. On Nov. 10, 1918, the day before the armistice ending the war was signed, Pvt. Willis Nusbaum, of Bluffton, was killed in France.

Although the armistice ended the shooting and shelling, the dying continued, particularly over the winter of 1918-19 as the Spanish Flu pandemic swept through crowded barracks and troop ships. Ultimately, there were more than 53,000 American combat deaths in World War I, while more than 63,000 deaths were attributed to non-combat causes. By the end of 1918, about 45,000 American troops had died of the Spanish Flu.

Less than a week after the end of the war, “sculptors of memorial shafts” were asked to submit designs to the city for consideration. Frank Cook, an employee of the engineering department, submitted one, not to be placed in Faurot Park as originally planned, but in the center of the Public Square. Noting the city needed a new street railway transfer station to replace a dilapidated bandstand/transfer station, Cook, in the words of the Times-Democrat, “conceived the idea of making the memorial answer all purposes.”

Cook’s plan was grandiose.

“The structure will consist of a high shaft on which a bronze figure of Victory offering up a sword is mounted, a reviewing stand led up to by four flights of stairs, a transfer station beneath the stand, and public restrooms in the excavation beneath the transfer station,” the Times-Democrat wrote Dec. 13, 1918. “The base of the shaft will contain four bronze tablets, three of which will contain the names of the fallen soldiers with the place, cause, and time of their death. The other tablet will contain the dedication.”

It was a grand plan – and it went nowhere. A proposal to include the county fell through. Delphos and Spencerville wanted their own memorials, and a canvass of small towns throughout the county showed most people opposed the memorial in Lima. The council committee planning it eventually dropped the idea. By the late spring of 1919, it was dead.

Meanwhile, in early 1920, discussions began on replacing the aging and inadequate Lima City Hospital on East Market Street west of the Ottawa River. Interestingly, a year earlier, in January 1919 at the height of the Spanish Flu pandemic and wrangling over the memorial, the Daily News had opined, “When all is said and done, what would be more appropriate than that the proposed memorial to the soldiers and marines should take the form of a County Soldiers and Marine Hospital.”

After several false starts on the hospital project, Lima voters in November 1927 were asked to approve $600,000 for a new hospital and $50,000 for “a Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Park contemplated to be established on what is now Hover Park for a park to be known as Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Park,” The Lima News wrote. The hospital issue passed; the memorial park issue did not.

On Feb. 3, 1931, the city leaders decided, “Lima’s new $600,000 municipal hospital, now being designed by architects, will be named the Lima Memorial hospital and will be dedicated to the soldiers, sailors and marines of the city who served in the World War.” The hospital, on Bellefontaine Avenue where the Lima Driving Park once stood, opened in May 1933.

SOURCE

This feature is a cooperative effort between the newspaper and the Allen County Museum and Historical Society.

LEARN MORE

See past Reminisce stories at limaohio.com/tag/reminisce

Reach Greg Hoersten at [email protected].